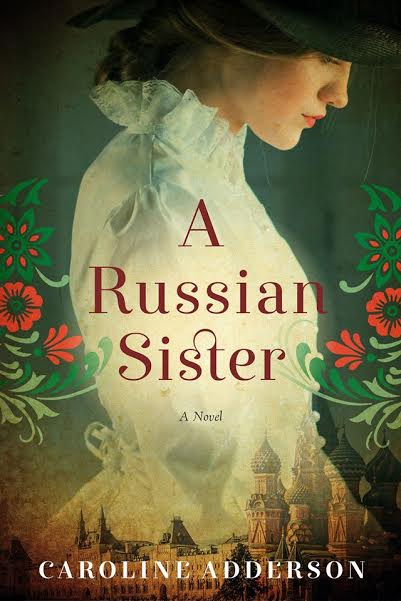

Caroline Adderson, the author of five novels and the Vancouver mentor for The Shoe Project, has had a new novel in August. “A Russian Sister” tells the true story behind Anton Chekhov’s play “The Seagull” through the eyes of his sister Masha.

CAROLINE ADDERSON | Photo: Jessica Wittman, TBC

Q. Could you start by telling us a little bit about your new novel, A Russian Sister?

A Russian Sister tells the true story behind Anton Chekhov’s play The Seagull through the eyes of his sister Masha. Masha lived with her famous brother and ran his household all his life. She also introduced him to her friends, many of whom fell in love with the handsome doctor-writer. One was the beautiful and much-younger Lika Mizanova, the future model for Nina in The Seagull.

The novel begins with that introduction, which sets off a convolution of unrequited love, jealousy, and scandal. Masha’s involvement in the relationship is just as turbulent: first, she facilitates it; then, she resents it. Briefly, she fears it. Finally, too late, she tries to prevent it. But this is only one side of the triangle that A Russian Sister dramatizes. The brother-sister relationship and the story of women’s friendship are just as important. Ultimately, A Russian Sister is a portrait of a 19th-century feminist, a strong woman pushing back against societal expectations and coming to value female relationships as much, or more than, the relationships she has been conditioned to expect with men.

Q. The book starts with a poignant sentence of the protagonist. –“I’m in mourning for my life. I’m unhappy”- Masha is a painter and the sister of a famous writer Anton Chekhov. Could you tell us a little bit about Masha?

That quote is actually from The Seagull. Each act of the novel starts with a line from the character Masha in the play that could just as easily be the thoughts and feelings of Masha in the novel, the playwright’s sister, amanuensis, housekeeper, secretary, bookkeeper, etc. As well as a talented painter, Masha was a teacher. She never married, despite receiving four proposals, all rejected by her brother. It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that Chekhov, a steadfast bachelor until a few years before he died, kept Masha close so that he could have a “wife” without the emotional complications of one. But given their difficult childhood, I think there was something more complex going on. I don’t want to say much more as the novel is really structured around Masha’s blossoming as an independent person despite her dependency on her brother.

Q. The story is set in Russia. You take us back to the end of the 19th century and describe a bygone era and a peculiar culture. What were the challenges of rebuilding a world with facts, real characters, and the imagination?

I didn’t have much problem obtaining the facts and details; those are fully available through reading and travel. The main challenge was translating fact to fiction. I wrote many drafts of the novel that were biography. I was terrified of barging into the consciousness of actual people, terrified of misrepresenting them. My breakthrough came when I realized that my Masha, Antosha, and Lika actually were fictional as much as any character I’ve created from scratch. I consider the novel a work of imagination based on fact. Though I conjecture about the background events, nothing is made up except Masha’s thoughts and feelings. For example, the physical abuse Chekhov suffered at the hands of their father is documented, but Masha’s memories of it in the novel are my creation. Lika’s backstory is also imagined but sadly, given her family situation, all too plausible.

Q. What did inspire you to write this story? How did you come up with the idea?

I’m a lifelong lover of Russian literature, particularly Chekhov. He’s come up at least twice in other novels, so it seemed like a natural progression to deepen my interest and try to fictionalize some aspect of his life. The true Lika-Nina story jumped out at me, but as a woman, I was naturally much more drawn to Masha and Lika’s side of it. This way, the novel came to be about Masha instead of her brother.

Q. The description of the landscape and nature is so vivid. I wonder if you have visited any of these places before?

Yes! I went to Russia in 2015. But obviously, my in-depth reading of Chekhov’s own work has also been invaluable in imagining that world.

Q. Has mentoring for The Shoe Project affected your writing in general, and how?

I would say that it has affected far more than my writing. The women I’ve worked with through the Shoe Project fill me with awe. They have survived war, oppression, and separation from loved ones; they’ve had to start again in a new language and culture. Every one of them is braver than I am. Many are better educated. Their respect and caring for each other despite their differences are a model for a kinder world. They have so much to offer. All I can do is write books.

By Simten Osken

Caroline Adderson is the author of five novels, two collections of short stories, as well as many books for young readers. Her work has received numerous award nominations, including the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, two Commonwealth Writers’ Prizes, the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Rogers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the Scotiabank Giller Prize longlist. Winner of three BC Book Prizes and three CBC Literary Awards, Caroline is also the recipient of the Marian Engel Award for mid-career achievement. She is proud to be the Vancouver mentor for The Shoe Project.