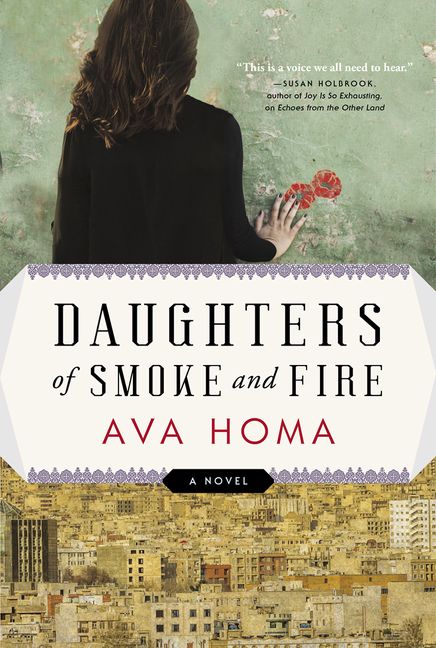

Ava Homa is a Kurdish-Canadian journalist and author. Her debut novel Daughters of Smoke and Fire (HarperCollins, May 2020) weaves fifty years of modern Kurdish history. It is an evocative portrait of lives and stakes faced by 40 million stateless Kurds and a powerful story that brilliantly illuminates the meaning of identity and the complex bond of family. Daughters of Smoke and Fire is the unforgettable, haunting story of a young woman’s fight for freedom and justice for her brother.

Ava Homa spoke with Shanga Karim, The Shoe Project’s alumna and Vancouver coordinator.

Ava Homa

Q: First of all, I would like to say congratulations to all the Kurds for having a powerful book written by a Kurdish woman. It is a great honour to interview you for “The Shoe Project.” The Globe and Mail named your debut novel one of the best new fictions of Spring. Who do you write for? Is Daughters of Smoke and Fire a letter of blood and tears from a Kurdish woman to other Kurdish women– or the world?

Thank you, Shanga. It is both. I dedicated my novel to Kurdish women “for flourishing in barren fields,” and I write for anyone who loves to read a good story set in a foreign country. Kurdish women tell me that they feel “seen” and “heard” through Daughters of Smoke and Fire, and that’s what I had aimed for. No one has written Kurdish women into literature. We must write ourselves into world literature.

I also believe we grow as humans when we see beyond what media and pop culture decide we should see. I am offering an authentic, original story set in an underrepresented world. I hope that the exposure would allow readers to see their humanity reflected back to them while travelling through books.

Because I transcended borders and dictatorship through reading, I hope to humbly give back to the world by allowing readers—anywhere they are on our planet—to “be” in Kurdistan through Daughters of Smoke and Fire.

Q: If your readers ask if the character Leila is Ava Homa, what would your answer be?

Readers have the right to bring their unique subjectivity to any literary text, and it’s common for readers to look for the authors in the books. I put my heart and soul into Daughters of Smoke and Fire, so I am there in every character, but it would be naïve to believe I wrote an autobiography. I could have easily published non-fiction—which has a larger readership than fiction.

I must add that minority novelists are more likely to be mistaken for their protagonists, and the world they present is often taken as the representation of their culture. The novelist Chimamanda Adichie powerfully articulates “the danger of a single story.” For example, the author of American Psycho won’t have to explain that he didn’t write an autobiography and that not all Americans are psychopaths.

We “ethnic” authors carry that burden in our consciousness constantly, the stereotypes, prejudices, and generalizations that surround us. Minority writers have to try thrice as hard to prove we have powerful imaginations, writing skills, and worthwhile stories to tell. Even when the gatekeepers can no longer deny our abilities, we are rejected because our stories allegedly don’t sell. To me, that’s insult added to injury. Publication houses and media outlets decide which books get the buzz.

With all that in mind, it sometimes horrifies me to think that readers would assume terrible things about my family based on my novel. Other times, I joke that if I knew everyone thinks I am Leila, I would have made her much more heroic and interesting. Either way, I remain aware of the tight corridors I have to navigate, but I refuse to tie myself into a knot and make myself small.

Q: How has Canadian support for your work been?

I am grateful to Jennifer Lambert at HarperCollins for her faith in my work. Because of the pandemic, I wasn’t able to travel and speak to Canadians directly. But I have received encouraging emails and reviews from critics and readers, which warm my heart.

Q: What is your purpose by mentioning all the famous Kurdish poets, filmmakers, and singers as Choman Hardi, Sherko Bekas, Bahmani Qubadi, and the beautiful voice of singer Naser Razazy?

My goal is to offer my reader a flavour of Kurdistan through fiction. It’s important for Westerners to know that oppressed societies also live complicated, nuanced, diverse, and full lives and have all sorts of artists and writers who enrich our ancient culture. Readers are amazed to see that although Kurds suffer atrocities, we have extremely loving and caring communities. They may also be surprised that we have the saddest history and the happiest upbeat music and are ready to dance and celebrate good fortune on any occasion.

Q: In November 2016, you gave a talk at the United Nations General Assembly on the high rates of self-immolation among Kurdish women in Iran. Does that put your life in danger? Has it had any influence on how you use your voice for other Kurdish women and humanity?

Standing up to dictatorship is very risky, but what I lost after that day was my strong belief in public advocacy. I have seen more results from my grassroots activism. No one, no country, no official did anything to prevent suicide among Kurdish women. Not every life is valued in our world. Not every loss is grieved. Media either doesn’t cover suicide or does so sensationally and irresponsibly.

So, I started an informal group of mostly Kurdish women (we do have two volunteer men, one of whom is Persian), and we have been developing curriculums and offering free workshops, encouraging participants to engage in difficult and important discussions about death by suicide and how to identify and help those at risk.

Q: What is your tip as a creative writing teacher and author of two great books to the BIPOC storytellers who want to start their writing journey in Canada with all the challenges they are facing?

It can be a long and difficult but worthwhile journey that will help you grow and learn significantly. Astutely observe how racism works against you but don’t let that dishearten you.

Master your craft so the gatekeepers can no longer ignore you. Your work is valuable. Canadian Literature is enriched by authentic, diverse, and powerful voices.

Q: I would like to hear your opinion about “The Shoe Project”. Is it a good source of writing and telling stories by immigrants and refugee women across Canada?

I think it is an impactful and important project. I admire Katherine Govier as a writer, a person, and the founder of this creative project, making the marginalized groups feel heard.

Q: How can you elicit comments from Kurdish readers? Are you getting responses from Westerners’ perspectives? Is there any attempt to translate the book into the Kurdish language?

Kurds have been gracious and supportive, especially women. It’s very encouraging when they tell me they see themselves in the book and feel their story is shared with the world. You said the same thing, and I am very happy to hear that. The book is being translated into Kurdish. We are also in conversation with Italian, Spanish, and Swedish translators. Wish us luck!

Q: Do you think the content/or style of your book can influence western readers in their understanding of eastern people, especially those who live in Canada or other western countries to promote communication, decrease discrimination, and racism by increasing understanding of eastern cultural background and suffering?

That’s my hope and my goal. I am sure Daughters of Smoke and Fire is one of many such steps.